THE DOUBLE TAKE - FALL 2017

"VISION / PERCEPTION"

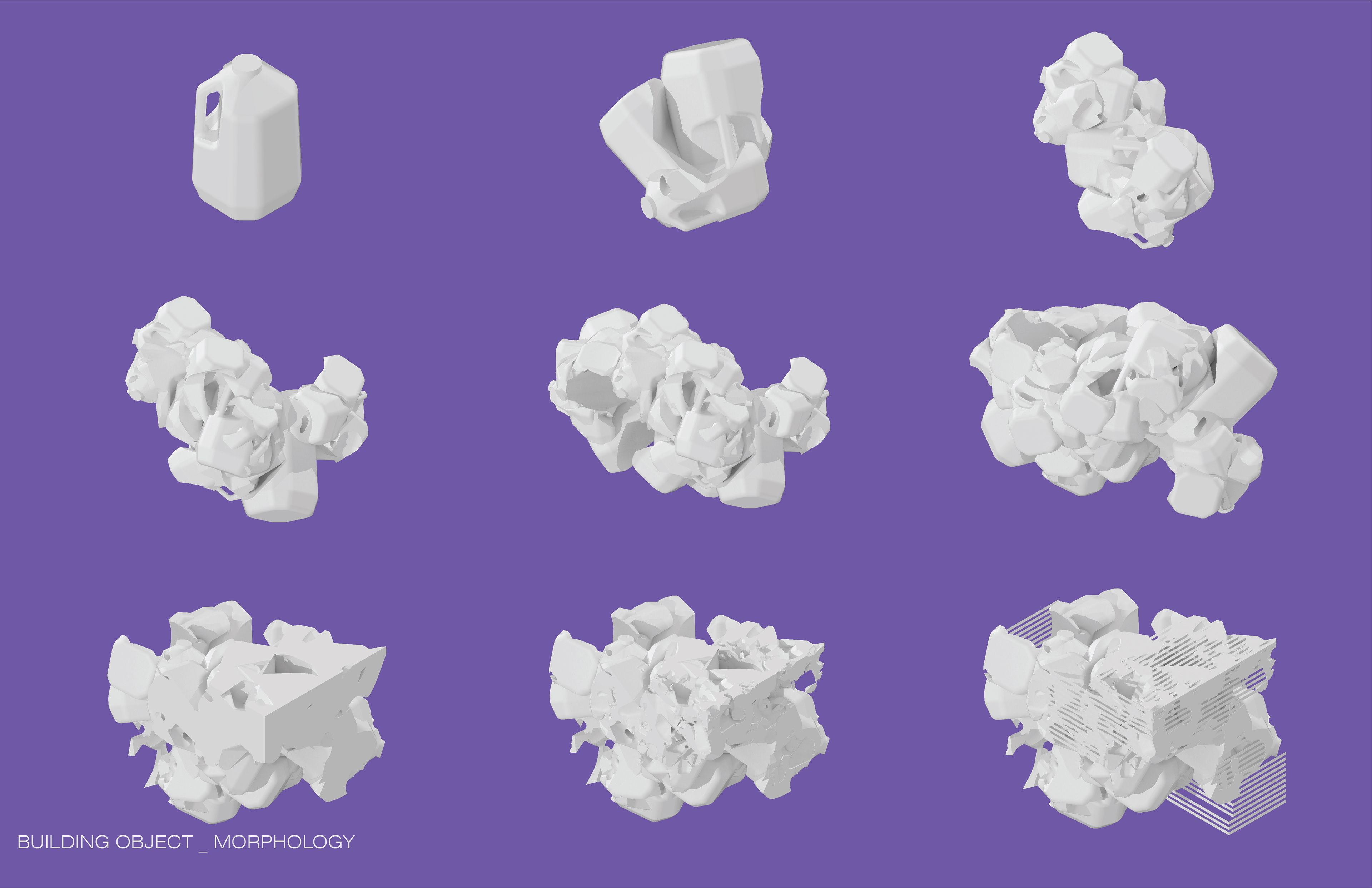

[Milk Jugs ; Rhino ; Adobe Illustrator]

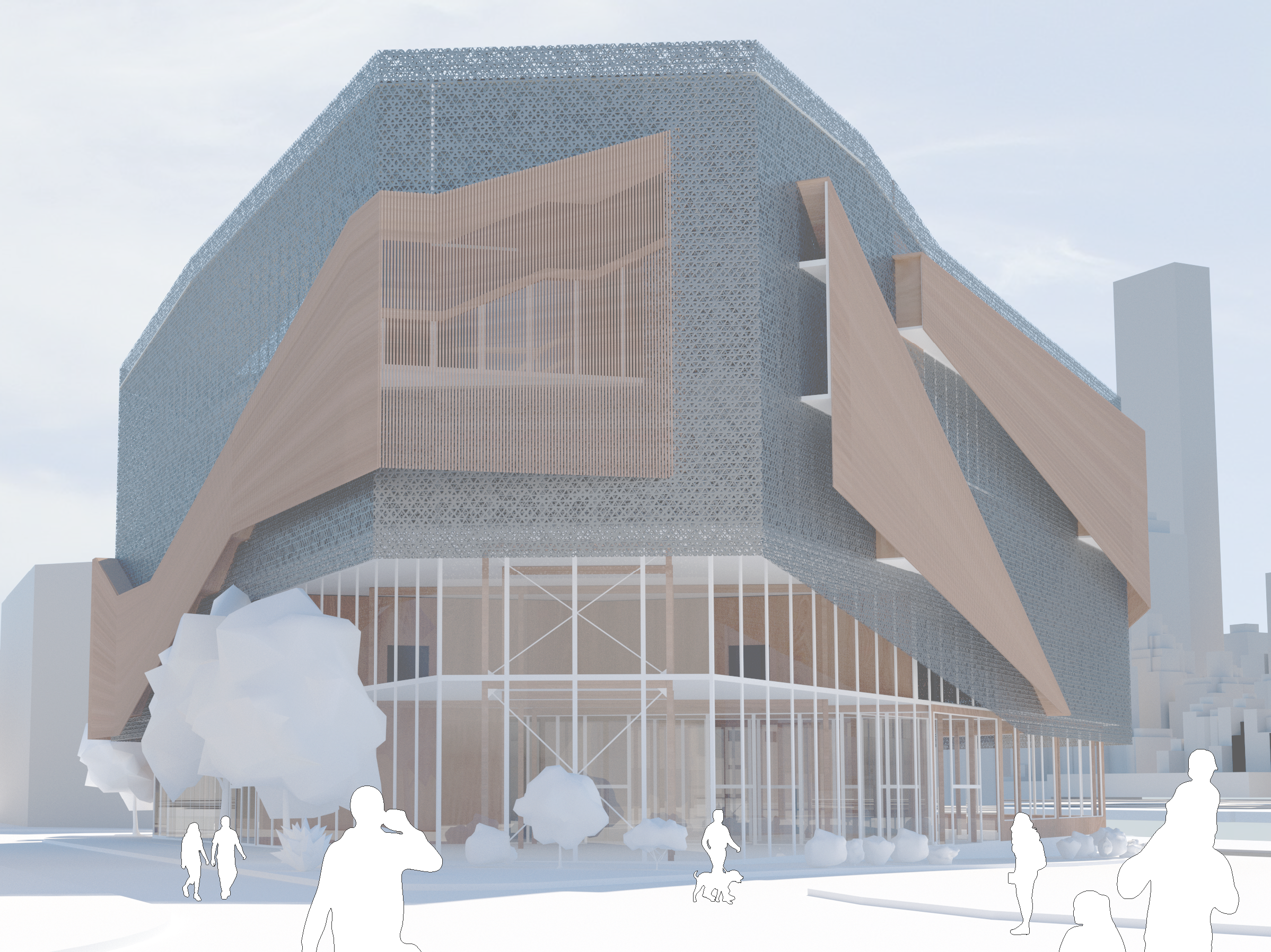

In studying Andy Warhol's appropriation of everyday objects, this studio focused on the concepts of "estrangement" and "defamiliarization." We were to create two objects that would act as an annex to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh as well as an educational center. The proposals consisted of a building object (the annex) and a ground object (the educational center) that were to question traditional architectural discourse and theory. While the building object would be created using an everyday object (in my case, milk jugs), the ground object was to either relate back to the building object or question something else entirely.

PROJECT TEXT_

How we read, interpret, and subsequently discuss architecture is related directly to how we see it. Both vision and perception play important roles in this understanding; where vision refers to the connection between thinking and seeing, perception is the rationalization of vision. This rationalization tends to reduces architecture to a series of easily understood concepts that undermine the object’s formal and theoretical properties. In order to preserve these properties, we must learn how to separate vision and perception when designing and talking about architecture.

Separating vision and perception is something that is not uncommon. For instance, images depicting the Great Pyramids of Giza in their present-day urban context distorts our traditional assumptions of formal and spatial associations as well as their historical context. In more contemporary work, Andy Warhol appropriates mundane objects and elevates them to art, portraying them simultaneously as something highly accessible (the commodity itself) and distant as it hangs in a gallery. This recontextualization relates directly to the Double Take where our perception of the object is so skewed that we must take a second glance. Implementing the Double Take - and thus separating vision and perception - in architecture involves two key points: complexity and representation. Complexity often comes in the form of contrasting formal elements and theoretical implementation in the design while representation refers to the way we portray the object in order to change the way we come to understand it. While both have always been present in architectural work, conceptual architecture begins to delineate vision and perception more than its practical counterparts. Piranesi’s Imaginary Prisons consisted of multiple perspectives that prevented the comprehension of the space as an unified whole, preventing the rationalization of the vision in its tracks. The dark and etched appearance of the drawings illustrated intent of disorientation - as well as the futility of attempts to escape. Yakov Chernikhov implemented complex interactions of form in his Constructivist-Era compositions, creating dynamism in his theoretical buildings that read as simultaneously industrial and monumental. The combination of color, high contrast shadow, and lines communicated these ideals while still maintaining a graphic quality. These examples of complexity and representation have been overshadowed by practical depictions of simplicity found in Modernist work that seem to refuse to separate rationalization from the design. Perception is thus “built-in,” leaving little room for conceptual discussion. In attempt to challenge this simplicity and separate vision from perception, my building and ground objects address complexity and representation in two different ways.

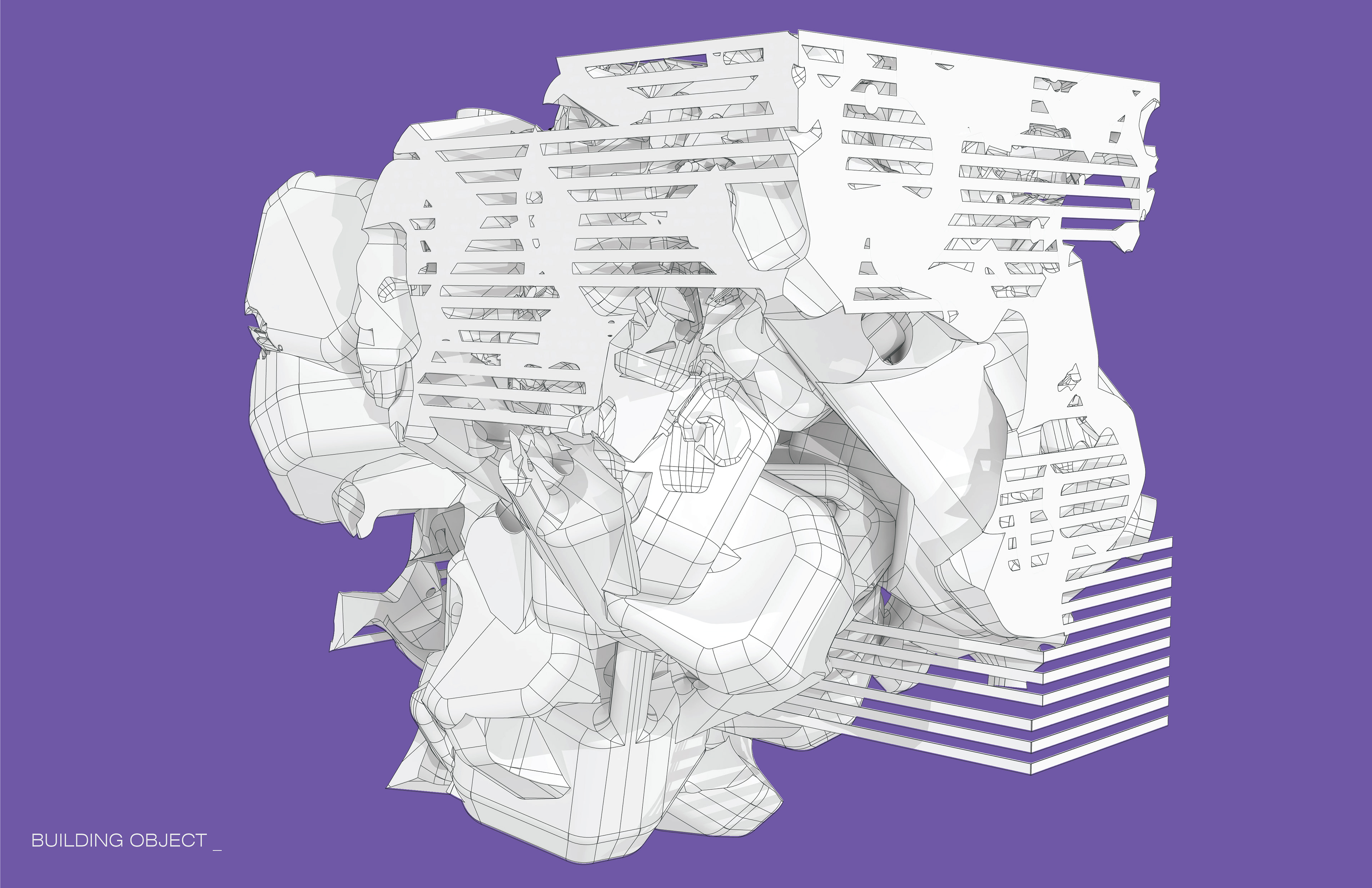

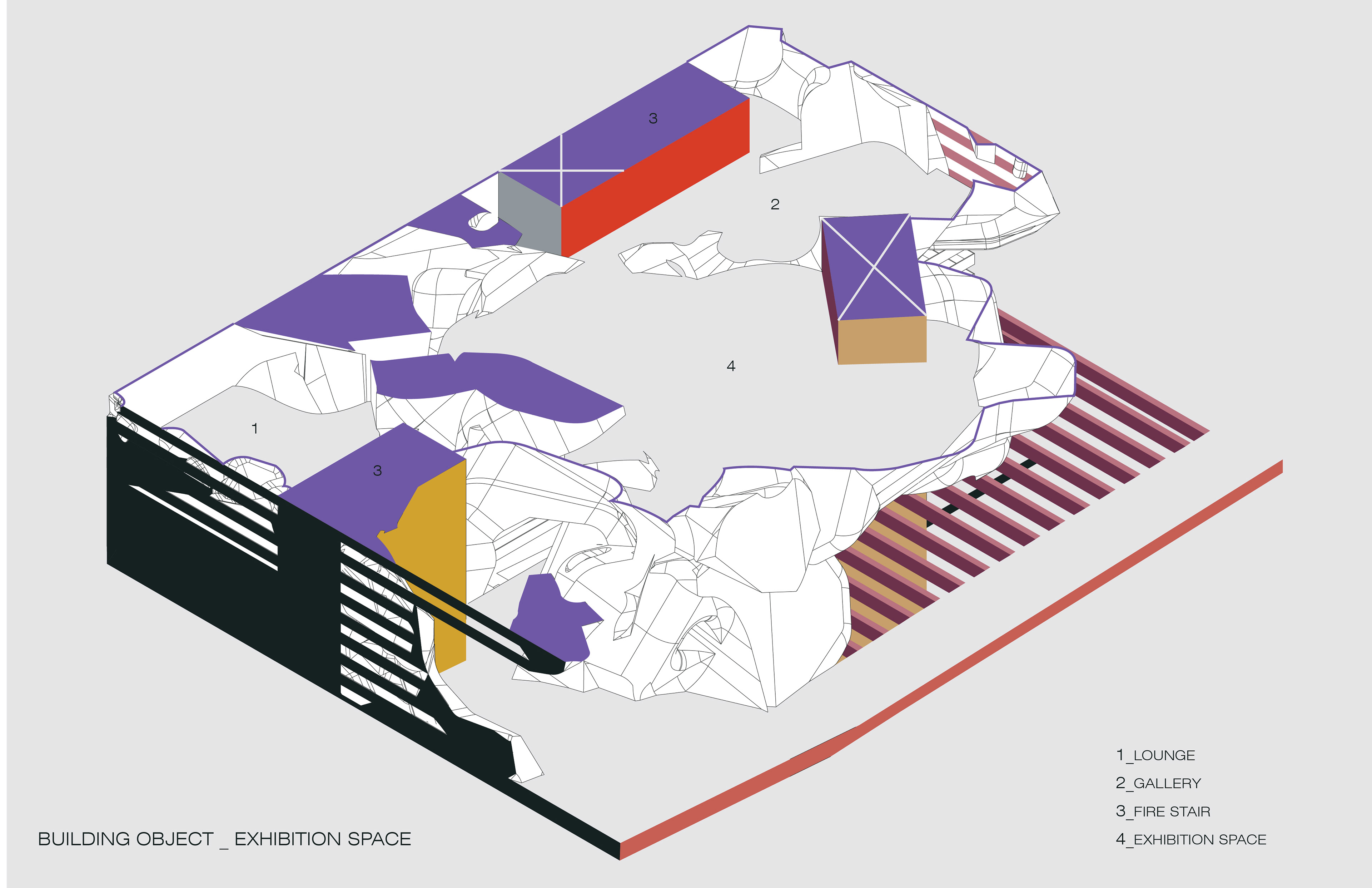

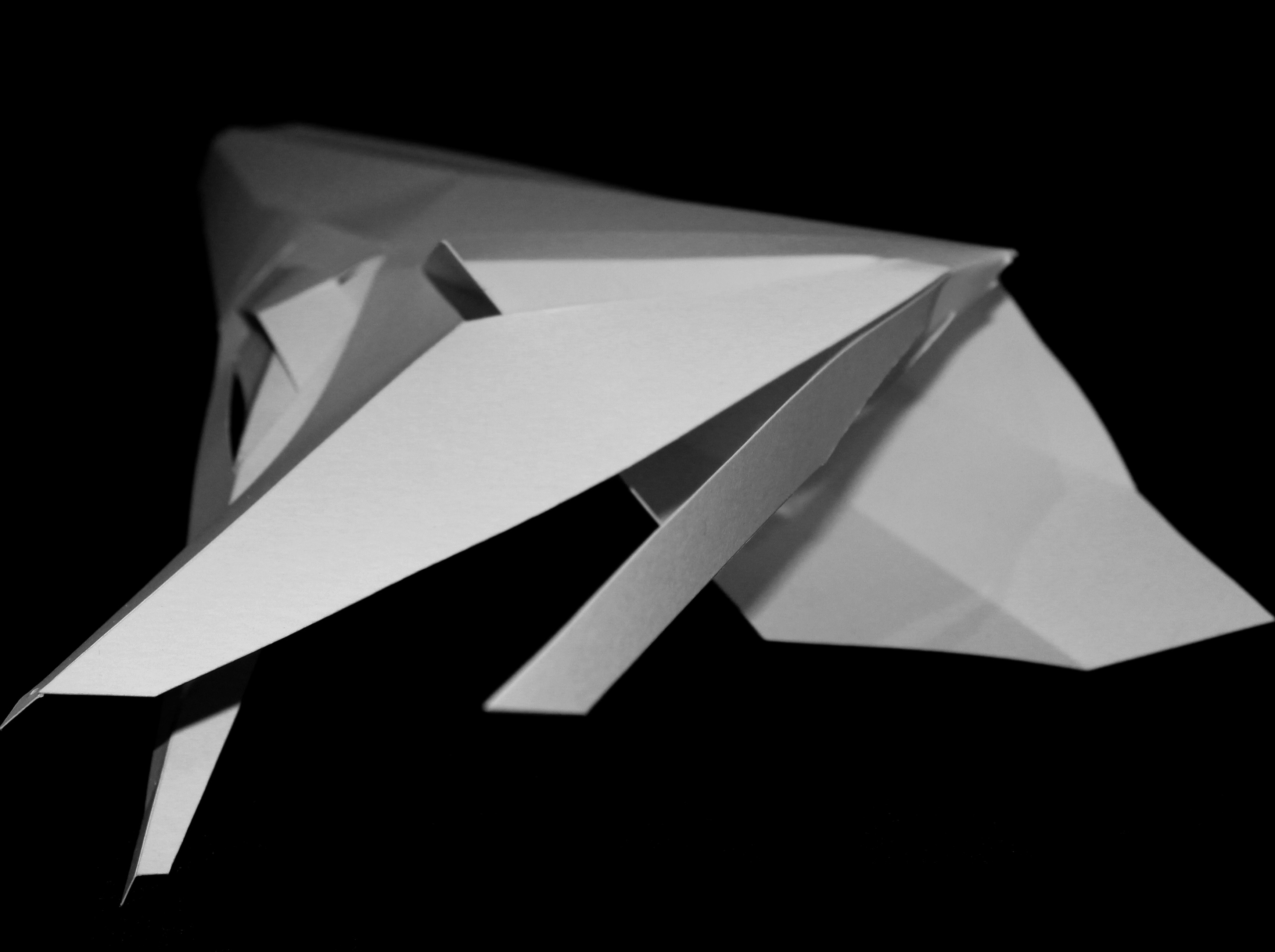

THE BUILDING OBJECT_

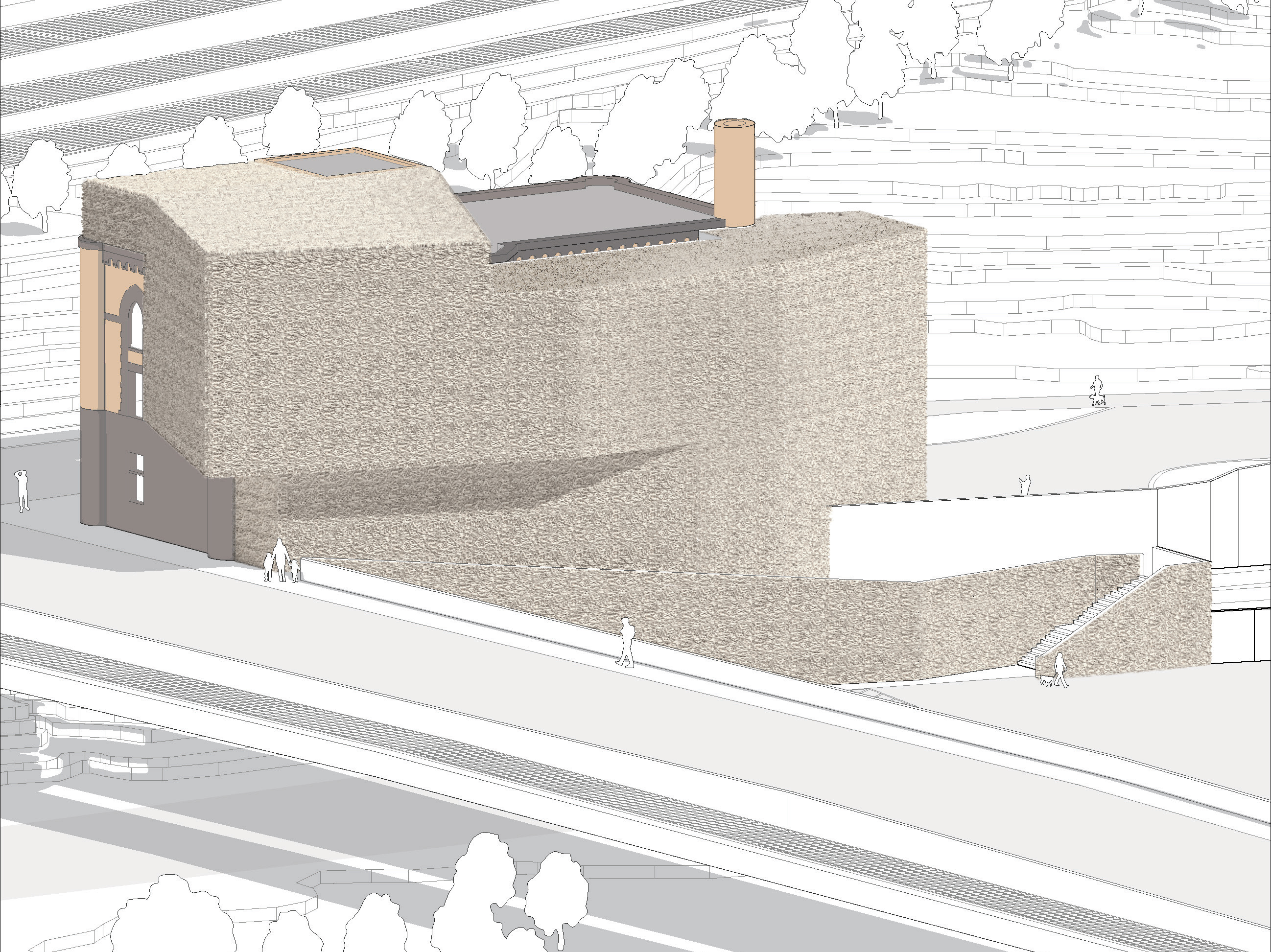

Beginning with dissected and reassembled milk jugs, my building object is a figural object in an orthogonal urban landscape. From the exterior, it reads as a conglomerate of unrelated yet fused pieces that disrupt the typical city datum lines. The contrast of these form with the linear elements on the facade allow the building to be read as two things at once : both figural and rational. The inability to discern if the object is supposed to one or the other sparks a Double Take, effectively limiting the rationalization of the object.

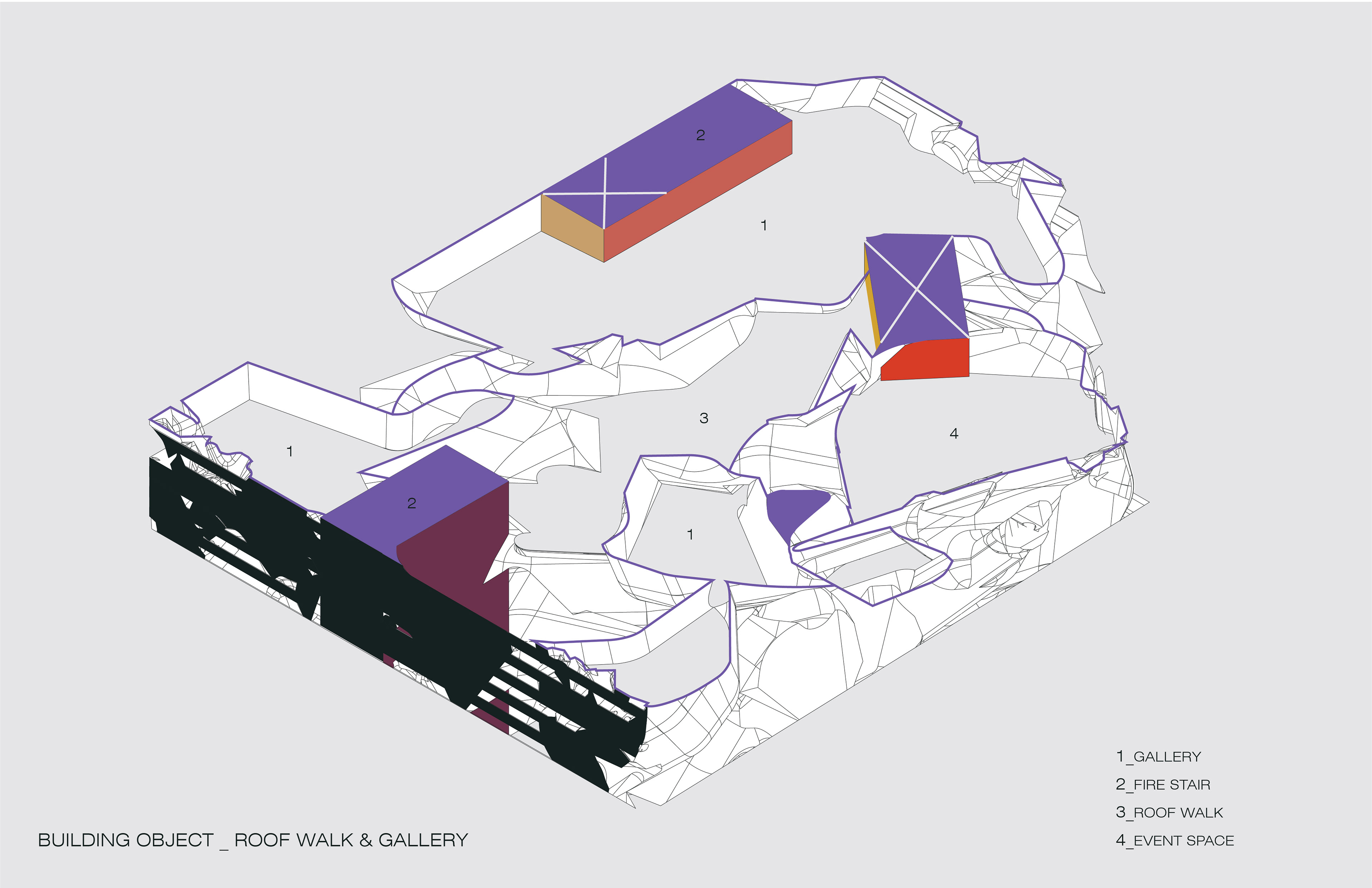

The figural elements intrude into the interior, creating spaces that are visually and physically obstructed. These elements separate the reality of the space - a rather linear path - with the perception of a winding one. In addition, the relatively solid exterior gives way to the “Roof Walk” - an outdoor gallery. This juxtaposition of solidity and openness creates formal complexity and skews the understanding that the building appears to be a solid mass.

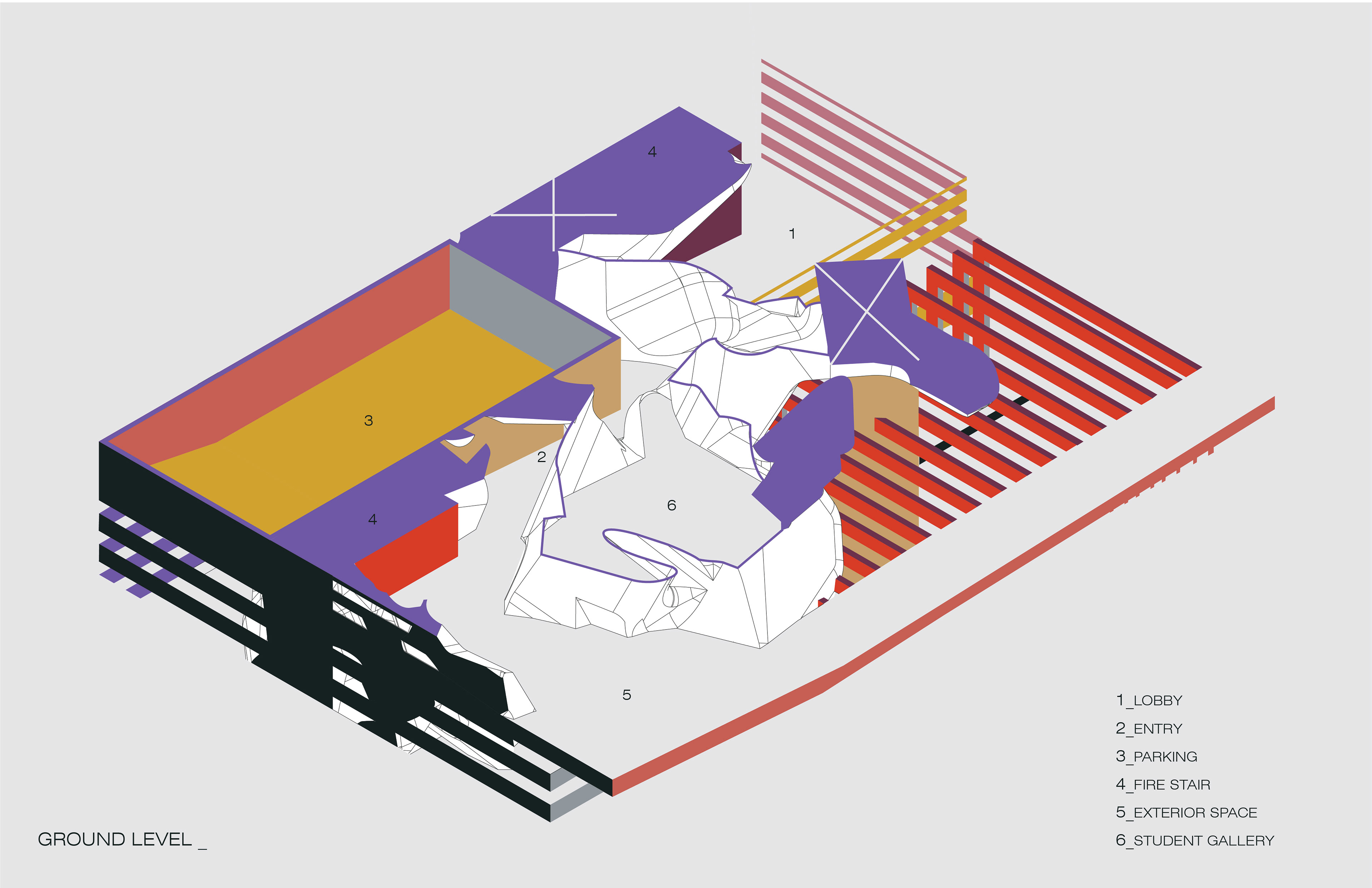

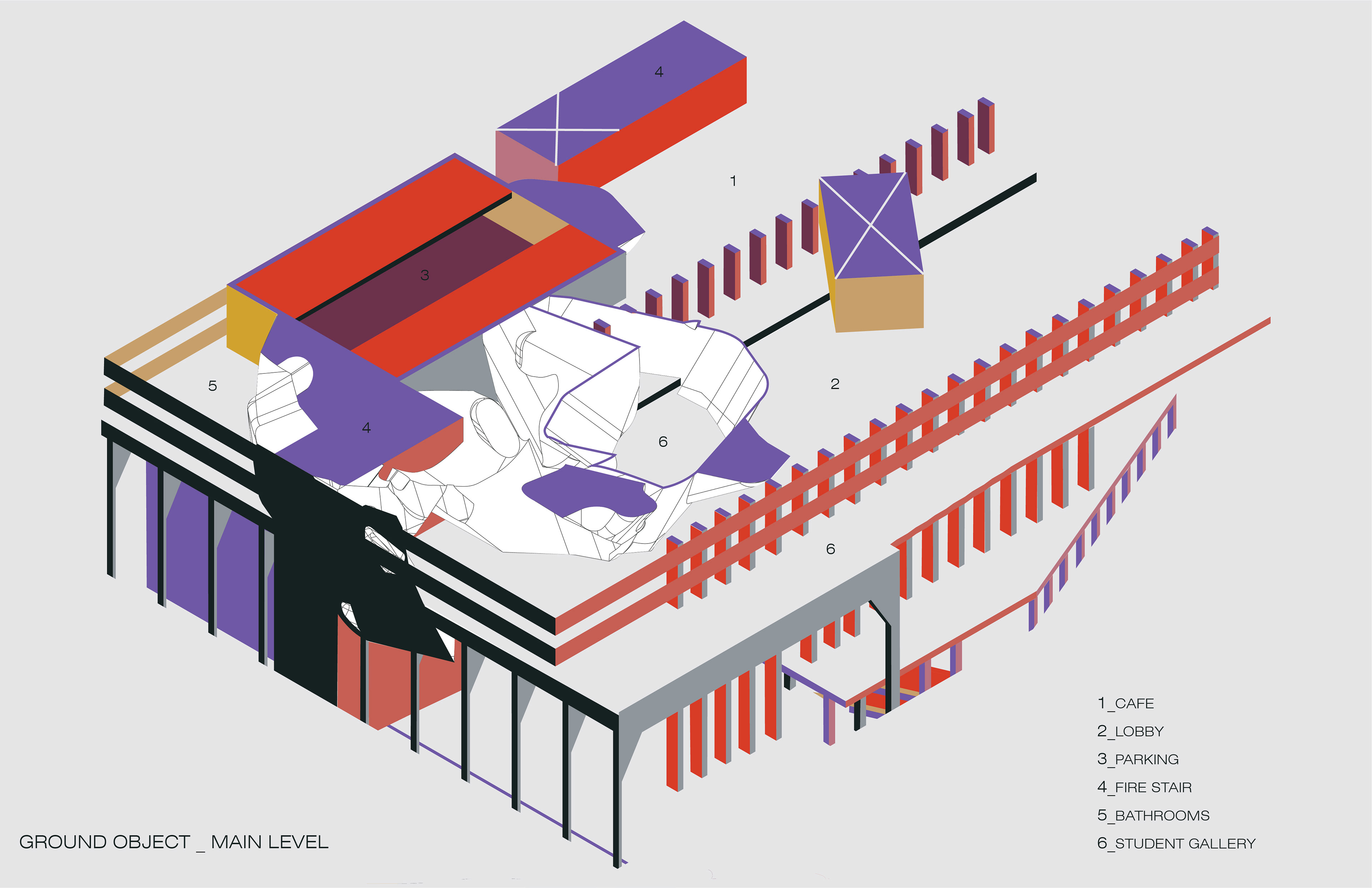

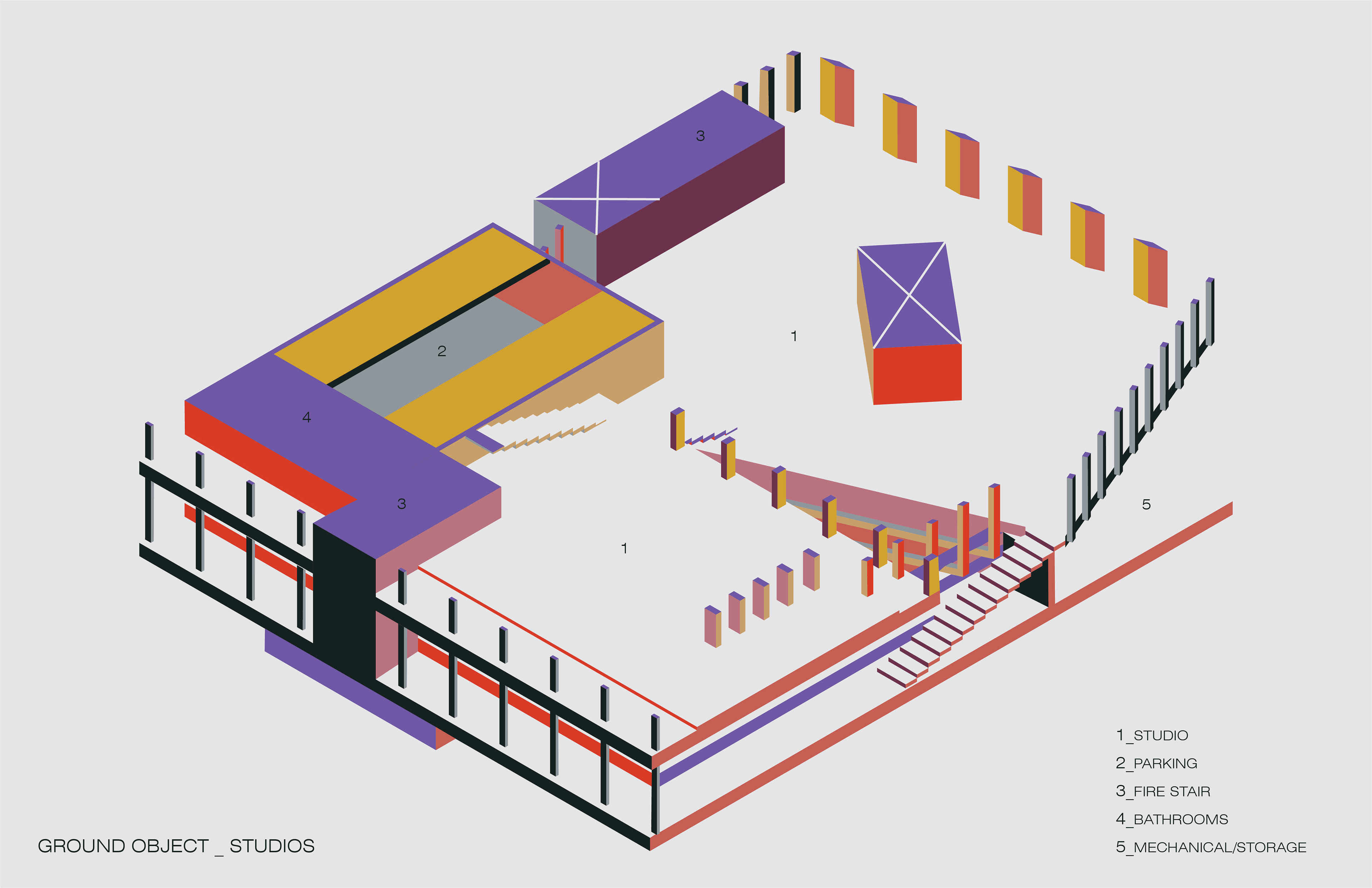

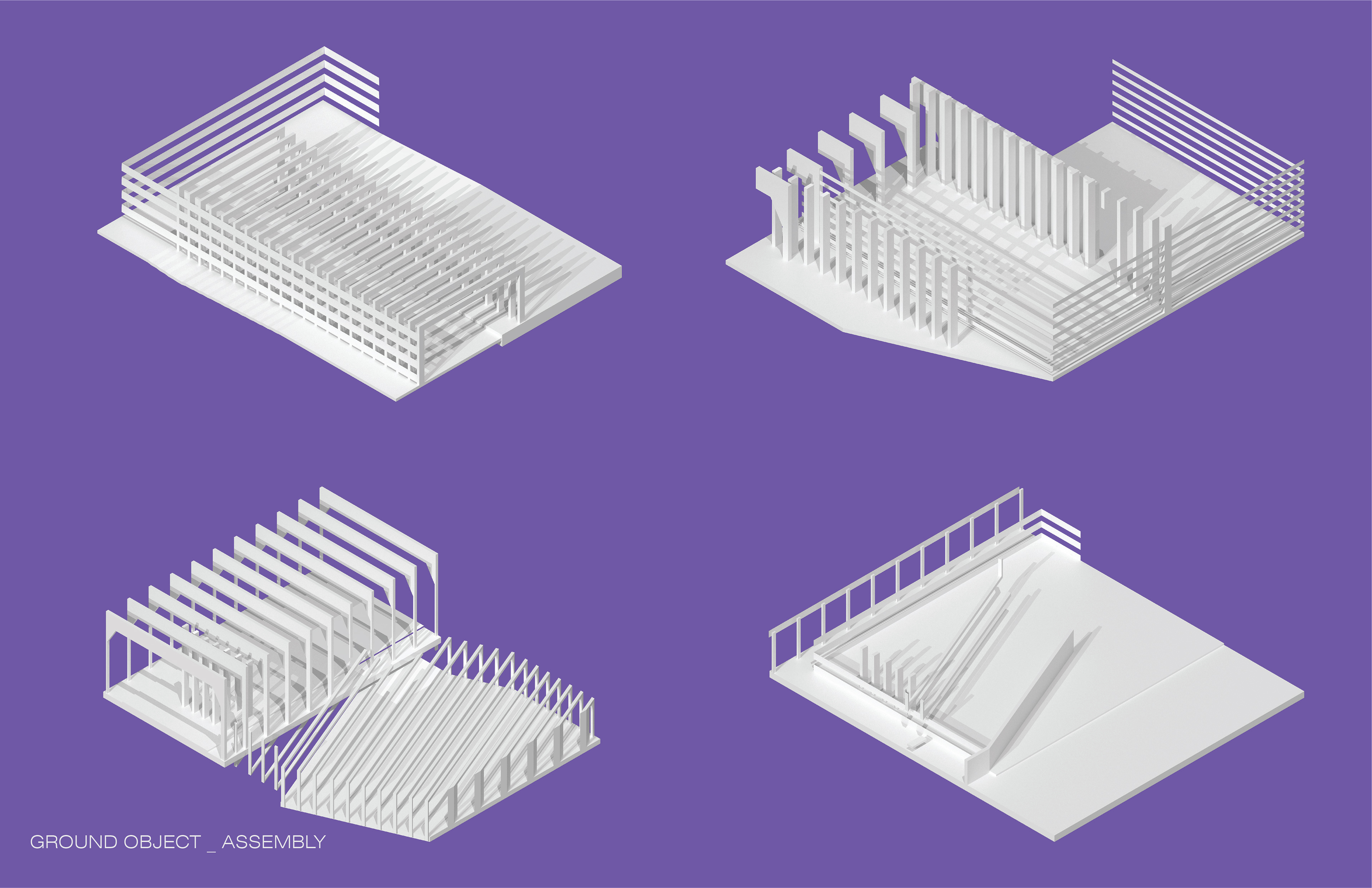

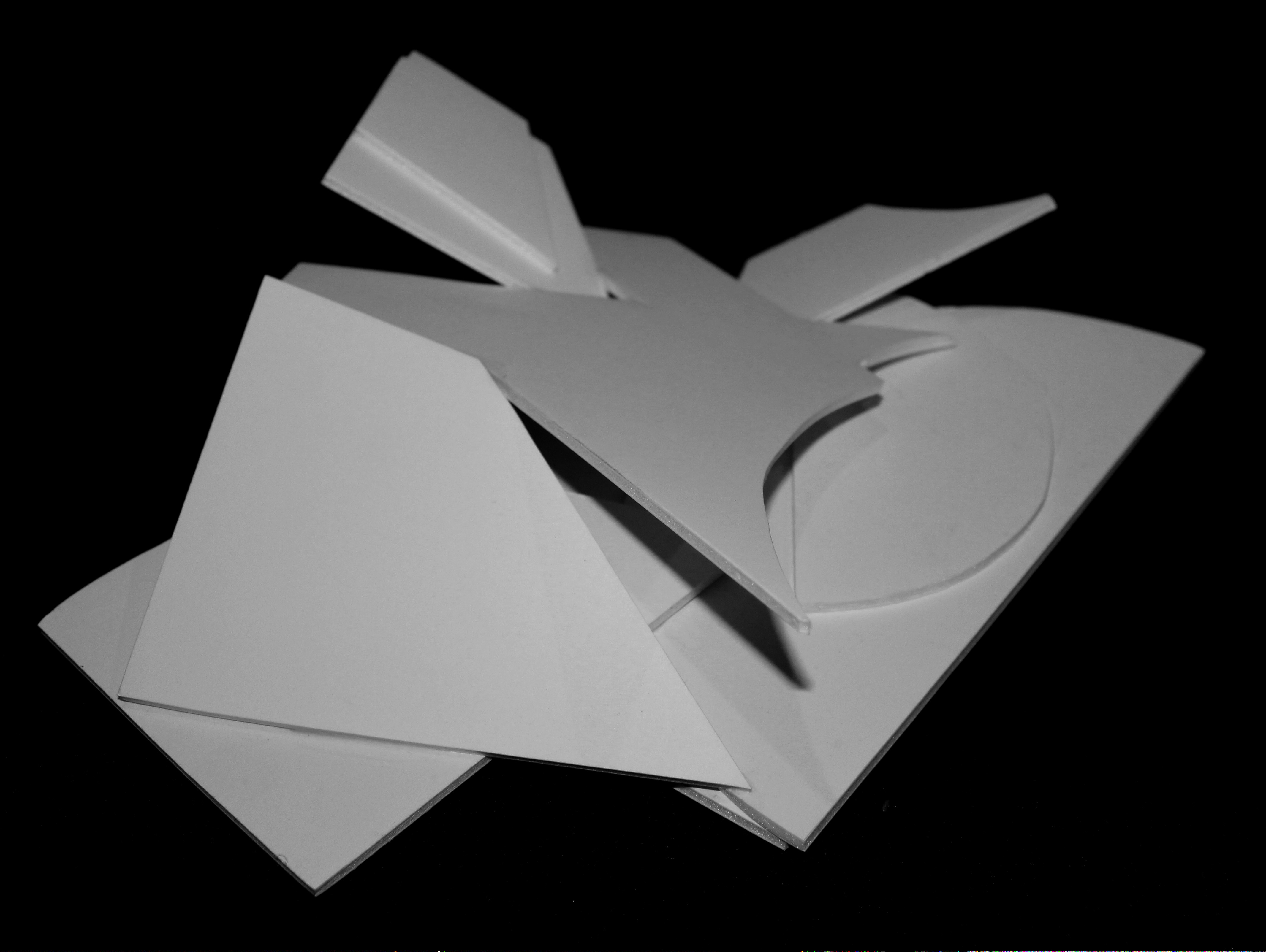

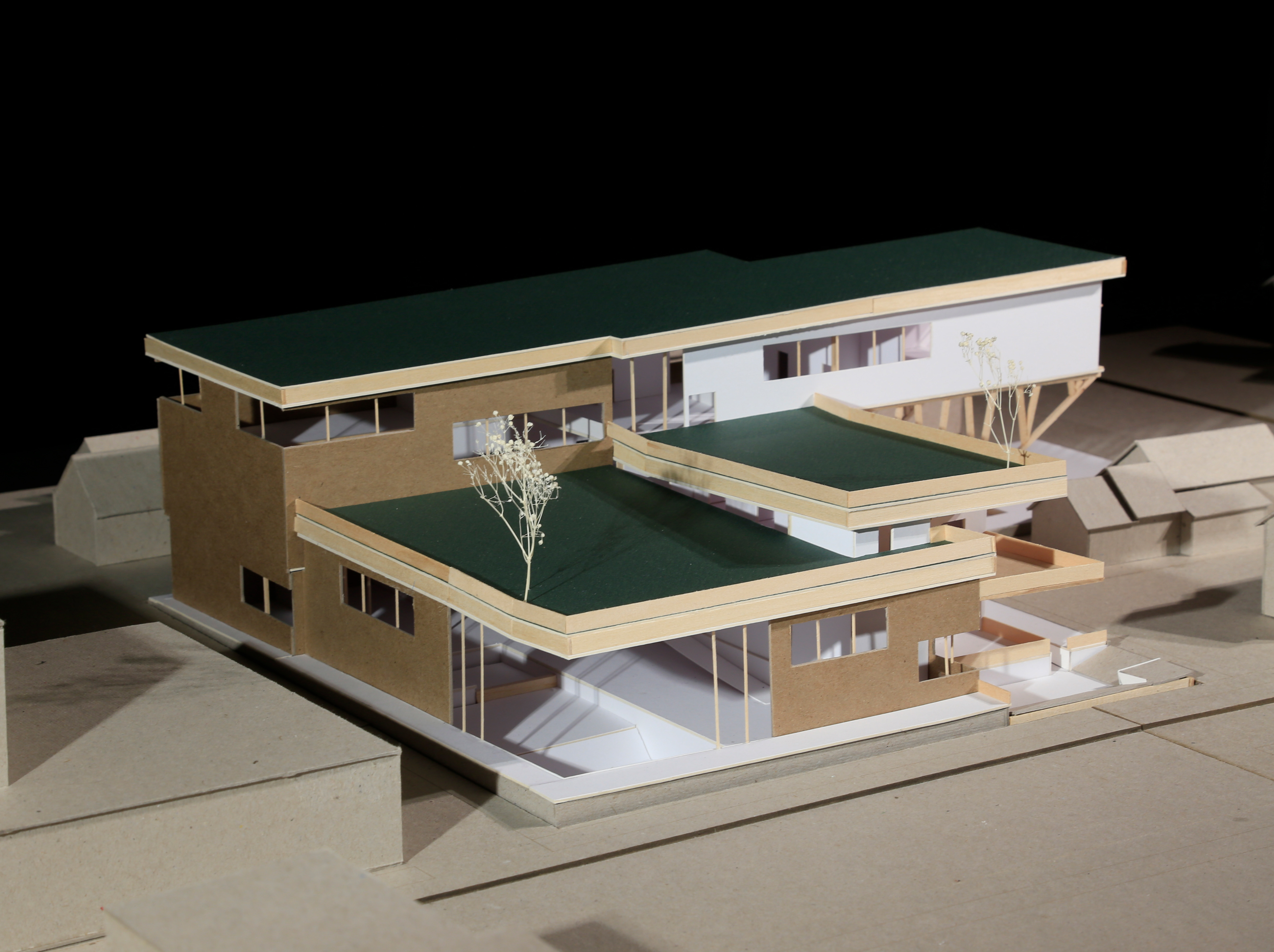

THE GROUND OBJECT_

By taking traditionally rationalizing elements such as lines and planes, the ground object’s formal characteristics resembles a wireframe consisting of vectors extending in multiple directions. These vectors interlock with one another within and around the ground object, dividing interior space and visually separating programmatic zones. This overlapping distorts the typical rationalizing effects by “flattening” the spaces and making it more difficult to discern what elements are in front and what are beyond. Each programmatic element resides in a “framed space” created by the intersection of the linear articulation and planar surfaces. The visual interactions between spaces can greatly impact the perception of the spaces as they all seem to blend together, blurring the boundaries between program elements and their functions.

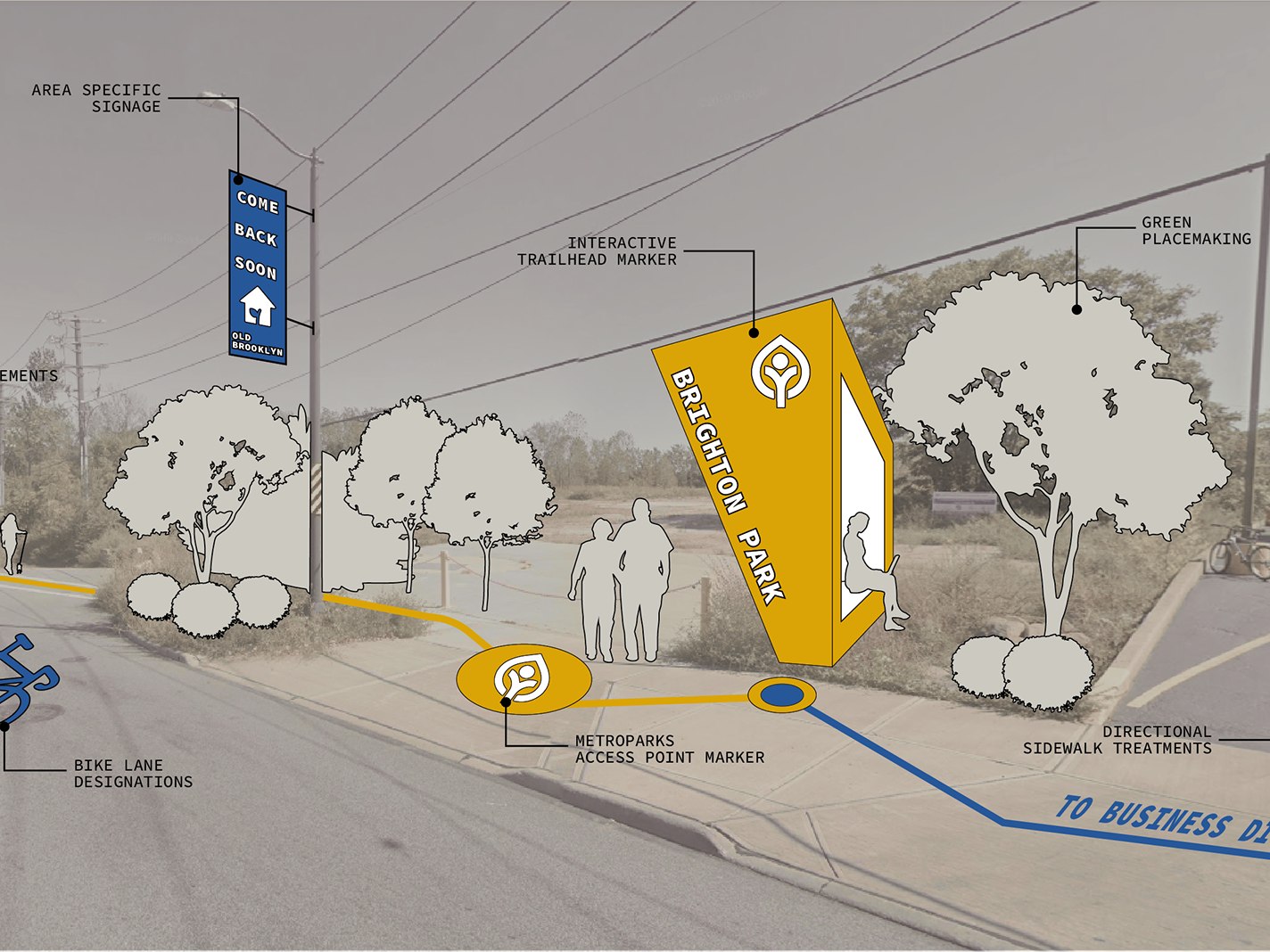

REPRESENTATION/INTERACTION_

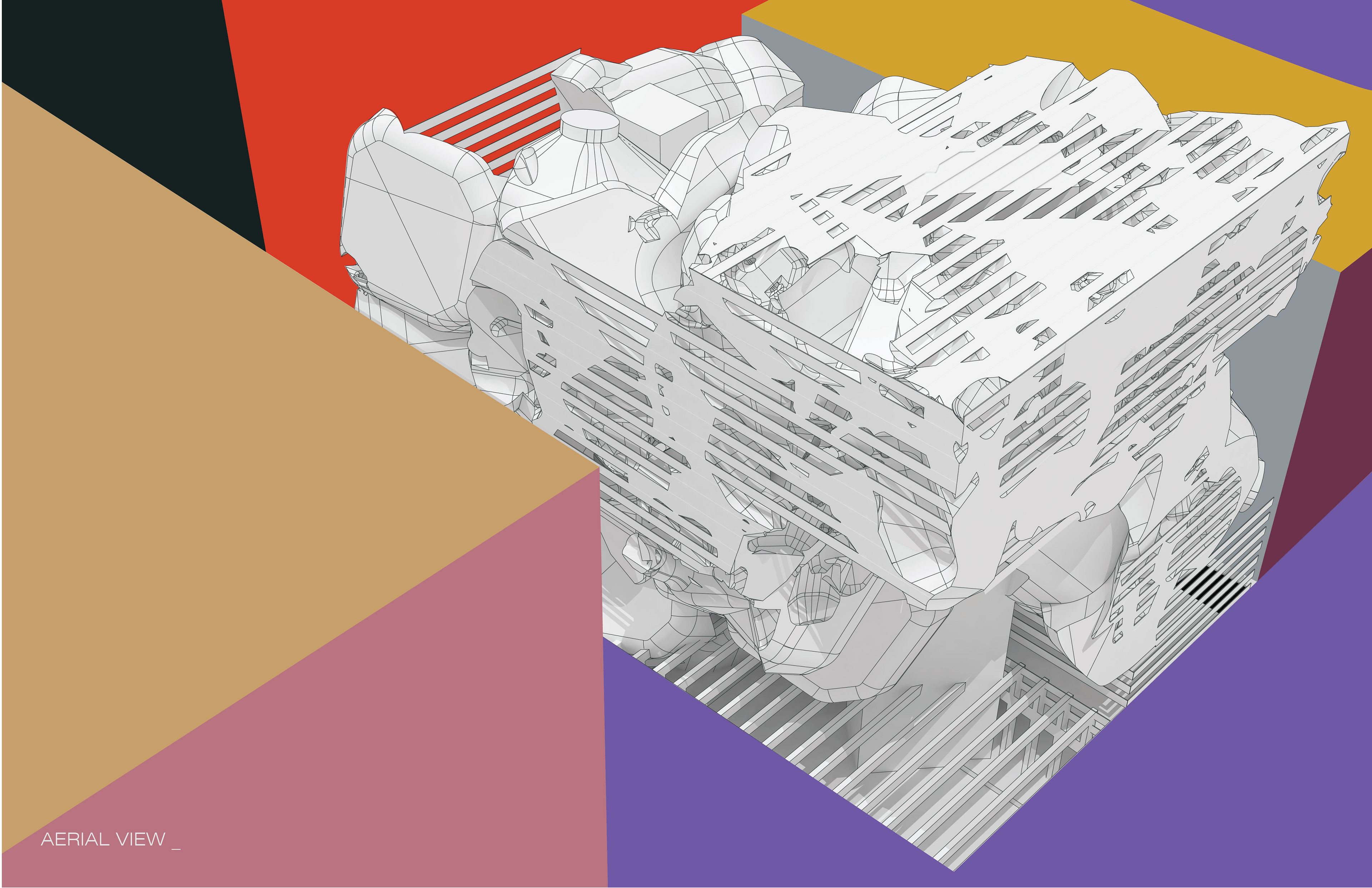

I used inspiration from both Pop and Constructivist art to develop my graphic style, recontextualizing my object in order to empathize contrast and the formal qualities of my design. My drawings rely very little on traditional architectural conventions and instead focus on the portrayal of the building as an object, not to be undermined in attempts to rationalize its spatial qualities.

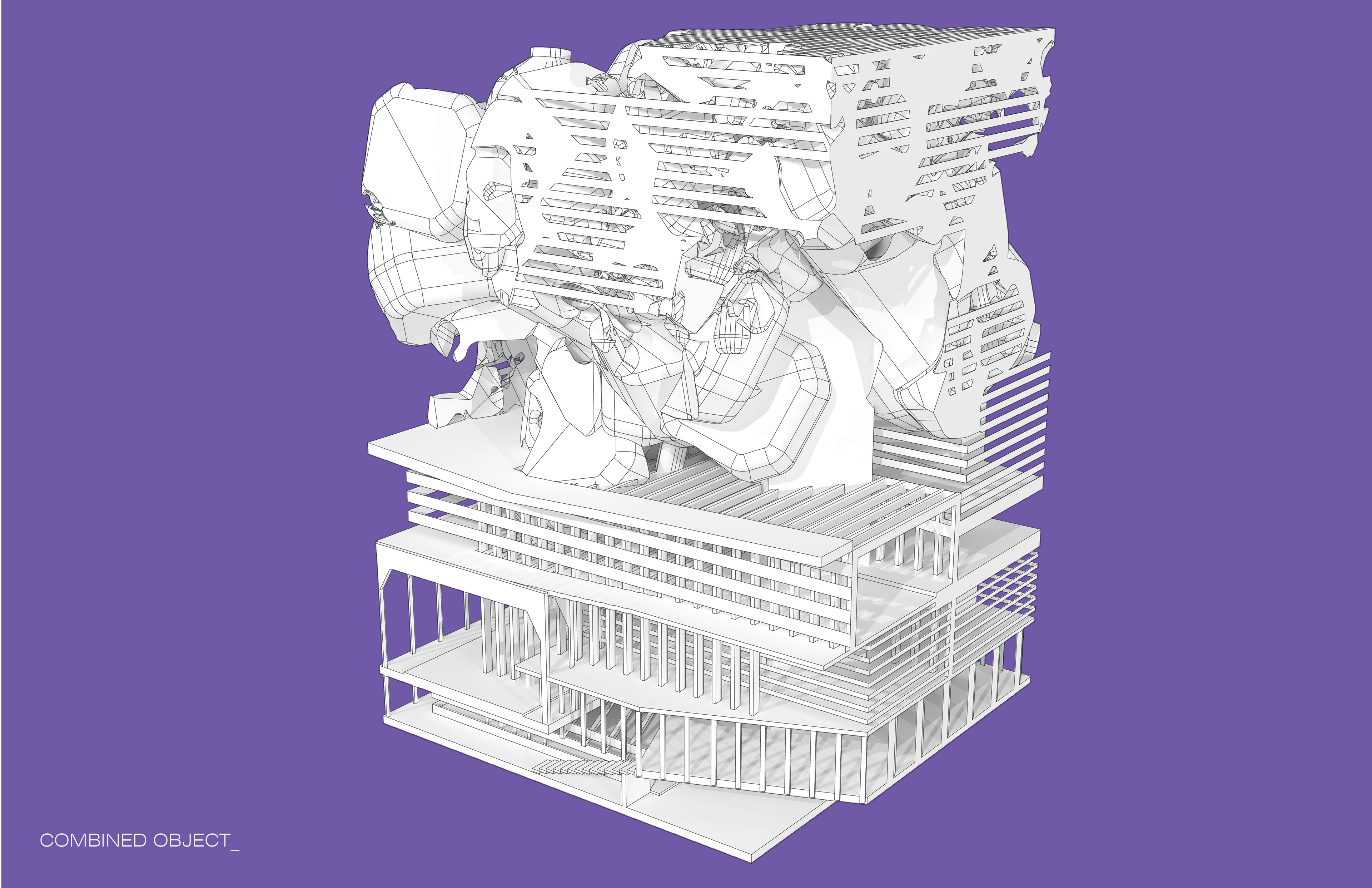

The contrast between the two objects is quite obvious: a rather curvilinear object is paired with one that is rectilinear. This juxtaposition is emphasized throughout the rest of the design by having clear separation between the two; while the building object physically penetrates the ground object, neither one has a direct response to one another.

In conclusion, Peter Eisenman states that creating a new form of architecture involves detaching what one sees from what one knows : “the eye from the mind.” This means we must let go of traditional - and often rationalizing - values of architecture in order to separate vision from perception, choosing instead to incorporate complexity and representation into the design. In doing so, endless possibilities emerge for interpretation and understanding, similar to the open interpretation found in the artwork of Andy Warhol.